Growth failing to translate into broad gains for majority Tanzanians, analysis

Despite steady economic expansion, Tanzania’s growth has not translated into meaningful improvements in living standards for a large share of the population, a new economic analysis has found.

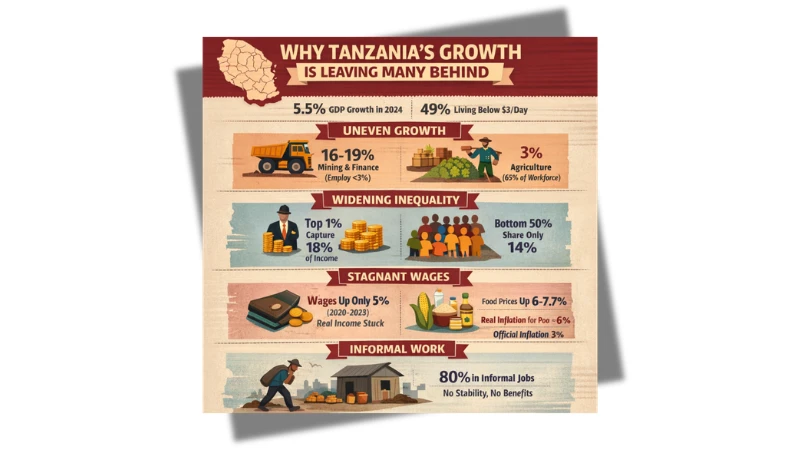

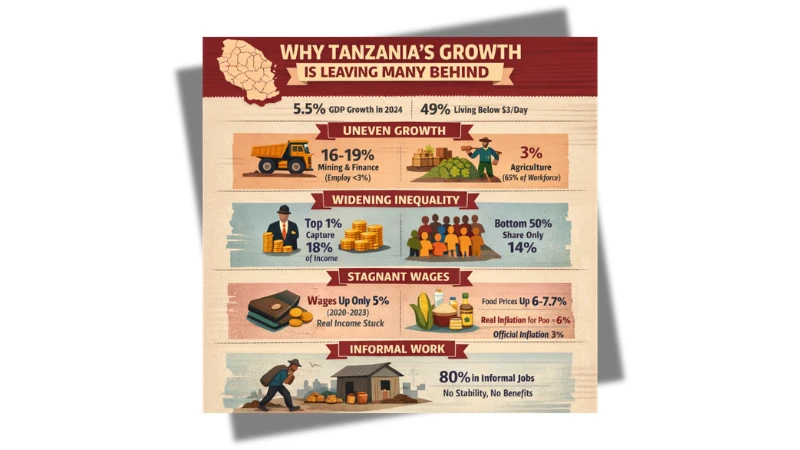

The report, based on a comprehensive review of GDP growth, inflation disparities and structural challenges between 2020 and 2025, shows that while the economy expanded by about 5.5 percent in 2024 and inflation remained around 3 percent, nearly half of Tanzanians still live below $3 a day.

The study, prepared by the Tanzania Investment and Consultant Group (TICGL), argues that the country’s growth pattern has been structurally skewed, benefiting capital-intensive sectors while leaving the majority of workers in low-productivity activities.

According to the analysis, Tanzania’s fastest-growing sectors—including mining, electricity generation and financial services—have been expanding at double-digit rates of between 16 and 19 percent. However, these sectors employ less than 3 percent of the workforce.

In contrast, agriculture, which employs about 65 percent of Tanzanians, has grown at around 3 percent—barely above the country’s population growth rate. The report notes that this mismatch between sectoral growth and employment distribution lies at the core of the country’s non-inclusive development pattern.

The findings also point to widening income concentration as the top 1 percent of earners account for nearly 18 percent of total income, while the bottom 50 percent share just 14 percent.

This means that a small fraction of the population captures a disproportionately large share of economic gains.

“When GDP grows by 5 or 6 percent, the distribution of those gains matters,” the report notes, adding that growth concentrated among higher-income groups does not automatically translate into broad-based improvements in welfare.

Wage data further underscores disconnect as between 2020 and 2025, GDP expanded by roughly 37 percent in nominal terms, while GDP per capita rose by about 24 percent.

However, average urban and rural wages increased by only around 5 percent over the same period, effectively remaining flat in real terms after adjusting for inflation.

The study also highlights disparities in inflation experience across income groups. While official headline inflation averaged around 3 percent, food prices rose between 6 and 7.7 percent. For low-income households, which spend up to 80 percent of their income on food, the effective inflation rate was significantly higher than the national average.

“Macroeconomic stability does not always reflect lived reality,” the report states, noting that rising food prices have eroded purchasing power among poorer households despite relatively low headline inflation.

Employment quality is another concern. An estimated 76 to 80 percent of workers are engaged in informal employment, characterised by low productivity, limited income security and lack of social protection. Even where new jobs have been created, many remain outside the formal sector and offer limited prospects for upward mobility.

Rapid population growth has further diluted gains. With population growth of about 3 percent annually, a GDP expansion of 5.5 percent translates into roughly 2.5 percent growth per capita.

The report argues that when inequality is factored in, the benefits for the average household are modest.

The analysis also points to stalled structural transformation. Although the share of the workforce in agriculture has declined from over 80 percent in the early 1990s to about 65 percent today, manufacturing’s contribution to GDP has remained stuck at around 8 to 9 percent for decades.

Many workers leaving agriculture have moved into informal urban services rather than higher-productivity industrial jobs.

On the fiscal side, limited government revenue constrains redistribution efforts.

Tax revenue stands at about 13 percent of GDP, below regional comparators, as a result, public spending on health, education and social protection remains limited, with less than 10 percent of poor households covered by formal social safety nets.

The report stresses that Tanzania’s growth achievements should not be dismissed, citing infrastructure expansion and macroeconomic stability as important foundations. However, it argues that the structure and distribution of growth must change to achieve meaningful poverty reduction.

It recommends targeted measures to raise agricultural productivity, stabilise food prices, expand manufacturing capacity, strengthen tax collection and broaden social protection coverage.

“Growth alone is not enough,” the analysis concludes. “The challenge is ensuring that economic expansion translates into rising real incomes and reduced vulnerability for ordinary Tanzanians.”

The report positions the country at a critical juncture, warning that without structural reforms, Tanzania risks sustaining macroeconomic stability while poverty and inequality persist.

Top Headlines

© 2026 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED