Online gender-based violence undermines women’s political participation in Tanzania

DESPITE Tanzania’s progress toward gender equality in politics, women continue to be significantly underrepresented in leadership roles. This gap is exacerbated by the rise of online harassment targeting women in politics, creating a hostile environment that discourages their participation. Laws such as the Cybercrimes Act of 2015, the Electronic and Postal Communications Act of 2010 (EPOCA), and the National Electoral Act of 2024 mandate gender balance in candidate nominations.

However, female politicians in Tanzania still face substantial challenges, including online abuse that undermines their electoral participation. This reveals that much more needs to be done to ensure women’s equal representation. One of the most pervasive issues faced by women in politics is harassment on digital platforms like social media, WhatsApp, and Telegram.

These attacks often involve the spread of false information, the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, and threatening messages. At political rallies, such abuse is strategically used to intimidate women and discredit them, reinforcing the idea that women do not belong in political spaces.

This discourages many women from pursuing political careers and silences those who are already involved.

According to the National Democratic Institute, women comprised only 9.5% of elected Members of Parliament (25 out of 264 MPs) in 2020. Special seats reserved for women accounted for 29% (113 women), bringing the total to 142 women (37%) out of 393 MPs. Similarly, the National Electoral Commission (NEC) report for 2020 shows that only 6.6% of elected councilors were women, with special seats making up 24.6%. In total, women represented just 29.2% of councilors nationwide.

Costs of gender based online violence

Women who run for political office often do so at great personal cost. Magdalena Sakaya, Deputy Secretary General of the Civic United Front (CUF), recounted her experience during the 2020 general election. Running for MP in the Kariua constituency, she endured a campaign of online abuse orchestrated by her male opponents, who spread false and damaging narratives about her on social media.

“As a Member of Parliament, I’ve faced this too,” Sakaya explains. “They’ll circulate video clips of your parliamentary contributions alongside insults made at campaign rallies. These attacks are so strategically spread that it’s difficult to trace them back to your opponent.”

Sakaya also shared how social media rumors affected her personal life, nearly costing her marriage. In 2022, her husband received a video falsely accusing her of having an affair with the National Party Chairperson.

Although her husband supported her, she expressed concern that such tactics would deter women from entering politics, making it harder to achieve equal representation. She advocates for stronger legislation to criminalize hate speech and personal attacks during political campaigns, arguing that individuals who engage in these acts should be banned from elections.

Shamira Mwakwenjula, 50, shared a similar experience when she ran for Mtimbila village chairperson in the Morogoro region in 2019. She received a barrage of derogatory messages via WhatsApp and Facebook, with villagers mocking her inability to have children as a way to discourage her candidacy.

Some of the posts, written in both Mwakwenjula’s local language and Swahili, cruelly questioned her qualifications for leadership and her lack of children, stating: “You're childless; how can you compete for leadership? You don't have a child, what is your focus? Whom do you want to defend? Why do you want to lead us? You didn't give your husband a child; we don't have a place for barren women in our village.”

Growing online violence against women

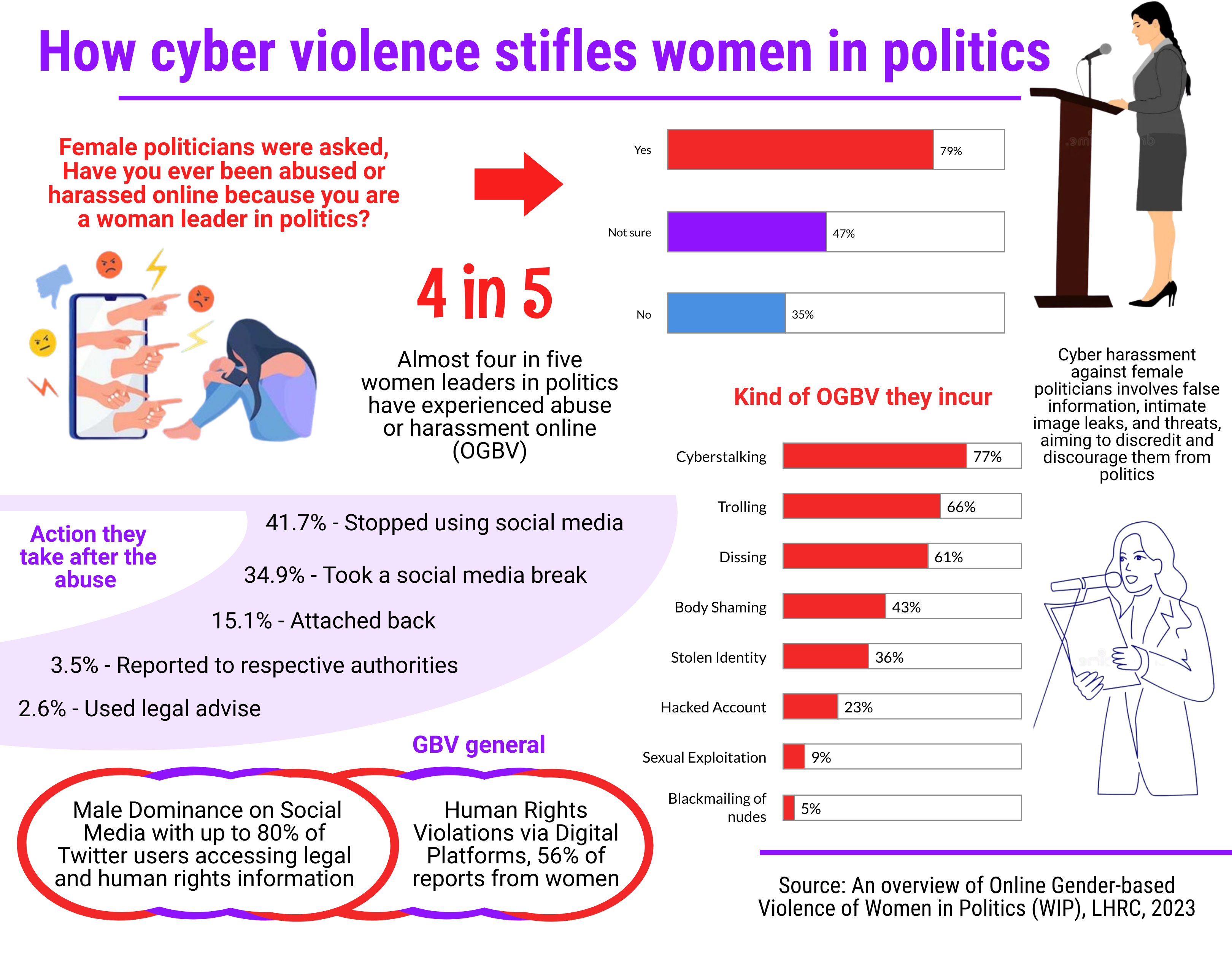

According to the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) June 2023 report, internet subscriptions in the country grew from 23.8 million in 2018 to 34 million by mid-2023. With this rise, online violence, especially targeting women, has also surged. A 2021 study by the African Parliamentary Union (APU) found that 80% of 224 women parliamentarians and staff from 50 countries, including Tanzania, experienced psychological violence, with 46% subjected to sexist attacks online.

Similarly, the Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC) Annual Report 2023 noted an increase in digital harassment, with women being disproportionately targeted. The rise in online violence has caused many women, including politicians, to withdraw from social media. The LHRC report shows that men are more active online than women. For example, 80% of users accessing legal aid and human rights information on Twitter, and 73.3% on Instagram, were men.

ACT Wazalendo leader, Doroth Semu, says the rise of social media has become a significant barrier to female politicians. Instead of being empowered, when they share their work on social media, they are often met with abuse, derogatory comments, and humiliation rather than encouragement, ultimately reducing the likelihood of their political engagement.

“There are many politicians on social media, but they avoid posting about politics for fear of insults, preventing the public from seeing their efforts and contributions. This lack of visibility often results in them not receiving votes during elections,” she said.

Asha D. Abinallah, Director General of Tech & Media Convergence (TMC), shared that in 2022, they conducted a study focusing on the state of online gender-based harassment targeting women leaders in politics. The research gathered opinions from over 340 women and found that more than 75% of women leaders had stopped using social media due to gender-based harassment.

The study also uncovered that the situation is worsening, with online users, particularly men, supporting and amplifying the harassment, creating fear among women and discouraging them from using social media to advocate for themselves, express their views, or seize various opportunities.

“For four months, we conducted focus group discussions to better understand the challenges women face and educate them on how to navigate these issues. We also learned a lot from their experiences and reached over 450 women,” says Abinallah.

Sophia Mwakagenda, a Member of Parliament for Rungwe Constituency, recalls the emotional toll of being defamed by an opponent who spread a false rumor that she had only one breast. The misinformation, aimed at portraying her as unfit for office, was widely circulated online, damaging her reputation and influencing voters. This situation almost extinguished her desire to serve until she received digital security training from the Tech & Media Convergence (TMC) in 2022.

“It’s like a battlefield where any weapon can be used, including malicious posts,” she explained. “The viral nature of such content amplifies the harm, and opponents often manipulate past personal photos to attack one’s character and credibility.”

Possible solutions

Several leaders have emphasized the need for resilience among female politicians. Doroth Semu, leader of ACT Wazalendo, encourages women to continue their political work despite online abuse, noting that such challenges are meant to discourage them.

Legal experts also urge women to take legal action against perpetrators. Tanzania’s Cybercrimes Act (2015) criminalizes digital harassment, and women are encouraged to sue those responsible for online abuse. While laws exist, advocates call for continuous training for law enforcement and judicial officials to effectively address cases of digital violence.

An advocate at the High Court of Tanzania and Deputy Chair of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) Tanzania, James Marenga, encourages women and female politicians to be fearless and assertive in the face of cyberbullying by suing those responsible. He emphasizes that digital abuse, whether through text, photos, or videos, can be legally challenged.

“Tanzania's Cybercrime Act (2015) criminalizes the use of electronic devices to harass others,” he says. “The law outlines procedures for collecting, preserving, and using electronic evidence in cyberbullying cases. It prohibits the sharing of defamatory messages and pornographic images and is supported by the Electronic and Postal Communications Law (2010) and the Penal Code.”

While these laws exist, there is also a need for continuous training for practitioners and professionals dealing with victims of digital violence, including law enforcement authorities, social and child healthcare staff, criminal justice actors, and members of the Judiciary.

At a recent event launching the “Women Now” project by the Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF), Minister of Community Development Dorothy Gwajima reaffirmed that women have the right to seek justice if harassed during elections. She highlighted Section 135 of Tanzania’s Penal Code, which classifies gender-based harassment in elections as a criminal offense, making Tanzania the first African country to officially recognize this issue.

Need for effective legislation

As the 2024 elections approach, there are increasing calls for stronger legislation to address online harassment and misinformation against women in politics. Felister Njau, a Member of Parliament for Special Seats (CHADEMA), advocates for laws that swiftly address election-related harassment. While the Cybercrimes Act criminalizes such behavior, it does not resolve election cases quickly enough, allowing perpetrators to win while victims suffer reputational harm.

Sophia Mwakagenda, have also called for better digital security training and education for women leaders. Mwakagenda emphasizes the importance of maintaining a professional online presence and using social media wisely, despite the risks. While online platforms offer opportunities for women to connect with voters, they must be supported by stronger legal frameworks that protect them from harassment and abuse.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights created a Resolution on the Protection of Women Against Digital Violence in Africa in 2022 which calls on all member states to promote and protect human and peoples' rights in Africa under Article 45 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (African Charter) by facilitating women’s access to education in digital technology domains in order to remove the digital gender gap, and ensure gender diversity in the tech sector;

States are called to ensure and facilitate effective cooperation between law enforcement authorities and service providers with regards to the identification of perpetrators and gathering of evidence, which should be in full compliance with fundamental rights and freedoms and data protection rules and implement victim friendly and gender-sensitive policies when handling cases of digital violence against women.

This article was created with financial support of the German Federal Foreign Office through Deutsche Welle.

Top Headlines

© 2026 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED