The new snake oil: antivenoms that are as useless as water

In sub-Saharan Africa patients face a “wild west” where treatments for snake bites cost the earth or don’t work

A Bureau of Investigative Journalism (London) dispatch by Paul Eccles, Andjela Milivojevic and Rachel Schraer, with additional reporting by Shafa’atu Suleiman and Laura Margottini

The implications for patients are severe. For instance, the test results suggest that medics could need more than 70 of these vials to treat the bites of some of the most dangerous snakes. That many doses would introduce two problems: delay, and high costs.

In reality a medic is very unlikely to administer that many vials. Firstly, a doctor will wait for hours between each dose of antivenom to see how a patient responds. So it would in all probability take too long for the medicine to work.

“Time is life,” said Calvete, adding: “The probability that you get out of the hospital with all your limbs is much higher if you don’t have to be treated with vial after vial.”

The cost is also prohibitive. A single Inoserp dose, purchased in Tanzania where healthcare isn’t always free, cost TBIJ US$66 (£50) – roughly a month’s earnings on the country’s minimum wage.

The testing reveals that problem is that, compared to its competitors, Inosan puts a fraction of the active ingredient needed into each vial of Inoserp.

Inoserp’s poor performance is not surprising for Calvete: he believes that Inoserp doesn’t live up to the claims it makes on its packaging. Calvete said he has spoken to Inosan about this “but they have not changed how they make their product”.

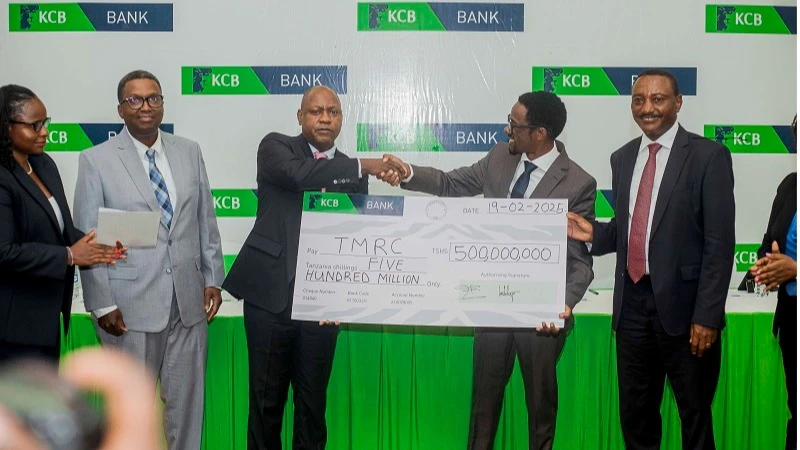

“You sell more vials, you get more money,” Calvete said.” Inosan has sold US$3.2 million worth of Inoserp to at least 13 sub-Saharan African countries over the past five years, according to shipping data analysed by TBIJ.

Inosan Biopharma told TBIJ that Inoserp has undergone several clinical trials and that “almost all” testing has shown “acceptable neutralisation and meets specifications with respect to other similar products”.

The firm added that even though its products contain a lower amount of active ingredient, “this does not indicate any reduction in neutralising potency or dilution. We assess the neutralising capacity irrespective of the protein content.”

It defended its pricing, saying that it had not yet made a profit on the antivenom and that intermediaries like wholesalers were responsible for some of the cost.

On the ground, doctors’ experiences vary. Dr Eugene Erulu, a medical practitioner from Kenya with more than 20 years’ experience in snakebites, refuses to use Inoserp.

However, others disagree. One is Dr Nicklaus Brandehoff, an emergency medicine physician and executive director with the Asclepius Snakebite Foundation – which runs clinics in Guinea and Sierra Leone.

Dr Brandehoff said Inosan’s product “seems to do its job pretty well”, adding that this was particularly true, for neurotoxic snake venom – the type that damages the nervous system, causing muscle weakness and paralysis.

Red flags in regulation and research

WHO has its own approval process as a safety net for countries without the means to check antivenoms. It threw out Inosan’s last application.

The global health agency said it was unable to guarantee that the benefits of using Inoserp would outweigh the risks, based on the evidence presented. The company is currently in the process of being assessed again.

Dr Abdul-Subulr Yakubu leads the cardiology unit at Ghana’s Tamale teaching hospital, but he ends up regularly treating snake bites; northern Ghana is snake country.

He often finds himself having to give a patient several times the recommended dose of antivenoms, including one made by the Indian company Vins. The WHO threw out Vins’ assessment of its sub-Saharan African products, like it did Inosan’s, in 2017.

“We’re not sure if we have to give large volumes because it’s not very effective,” Dr Yakubu said.

He argued that, after all, there were many other factors that can complicate treating a snake bite.

Many snakebite patients who go to hospital will commonly have been to local healers first, delaying their treatment and sometimes introducing infections. Some come in too late for antivenom to work. Others don’t know what kind of snake has bitten them, making it harder to give the best treatment.

Vins applied for a WHO recommendation for its antivenom in 2016. The process was cancelled when, among other issues, the company submitted a paper on its medicine supposedly by two respected researchers, both of whom denied having any involvement in the study.

Professor Kate Jackson, one of the listed authors on the paper, confirmed: “I didn’t collect those snakes and they don’t exist in [the Republic of the] Congo.” She said she did not recall Vins contacting her about the paper.

Vins claimed that “a senior employee” presented the research under Jackson’s name and their contract was “immediately terminated” when the company found out.

“Since then, we have further strengthened our protocols to ensure that this is never repeated … We agree that indulging in such acts calls for the validity of the data to be questioned,” noted the firm.

It’s another example of questionable practices and the scarcity of reliable research. Health workers told TBIJ that, without it, they try the available antivenom and hope for the best – without ever being sure if it was the medicine, or the patient’s luck, that had the most effect.

TBIJ tested a Vins vial purchased in Uganda. It contained far more of the active ingredient than Inosan’s product does.

Having performed poorly in tests in the past, Vins was overall the best-performing antivenom in TBIJ’s testing.

Against three out of four snakes, it outperformed one of the only antivenoms approved by the WHO for use against some snakes in sub-Saharan Africa – PANAF, the antivenom made by Premium Serums for use against snakes in the region.

However, Calvete said that even the best antivenoms available in sub-Saharan Africa “could be better and should be better”.

Vins has re-applied to the WHO and is currently going through the agency’s approval process again.

Falling short

While ineffective antivenom can have deadly consequences, it’s really the last of many hurdles between a snakebite patient and survival. First patients have to get to a clinic in time – and hope that the clinic actually has a suitable antivenom.

Dr Nicholas Amani Hamman, medical director of Nigeria’s Kaltungo Snakebite Hospital and Research Centre, is only too aware that antivenom shortages are a huge problem across the African continent. Just this autumn, he had to watch four-year-old boy Desire die while waiting for a second dose of antivenom.

Desire had been taken to the hospital after being bitten by a snake on his way home from helping on the farm, and given one bottle of EchiTAb-Plus-ICP, an antivenom designed to treat Nigerian snakes.

Too bad, that wasn’t enough and the boy’s blood wasn’t clotting, but Dr Nicholas didn’t have any more to give. His hospital urgently appealed to officials and charities for the medicine, but it didn’t come in time to save the boy.

In other cases, shortages open the door to inappropriate, substandard or even fake antivenom flooding in.

A few hours’ drive north, Professor Abdulrazaq Habib heads up the Nigerian Snakebite Research Intervention Centre. When antivenom is out of stock in his hospital, he will write a prescription for patients to take to a pharmacy.

A patient may have to “go back to his or her village and then sell a goat or a sheep or a cow” in order to afford treatment. Even then, there’s no guarantee that they’ll get the right one.

Over the years, Habib has seen everything from genuine medicines that don’t work for the snakes in the region to fake products and to asthma medication sold as antivenom because the bottles look similar.

When TBIJ sent a reporter to a pharmacy in the northwest of Nigeria, we were offered antivenoms suitable for Indian snakes and a rabies vaccine. Neither would have helped against a snake bite.

Neglected by the world

Very little antivenom is manufactured in sub-Saharan Africa. It’s estimated the region receives as little as 2.5 per cent of the antivenom it needs. It has come to depend on imports, creating what Thea Litschka-Koen and other experts call the “wild west”. Sloppy practices and unscrupulous manufacturers have thrived.

“Listen, let’s not paint every manufacturer with the same brush. There are some phenomenal manufacturers out there … We mustn’t think that everybody out there who’s making antivenom is doing it for a quick buck. That’s not true,” said Litschka-Koen, adding: “The reason for this entire shitshow is that snakebite was totally ignored.”

Snakebite is known as the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases. That’s a classification given to a group of preventable and treatable diseases.

Despite its toll, snakebite only cemented its place on the WHO’s list of priority neglected tropical diseases in 2017, years after other diseases.

Most countries in the world have agreed to a goal of halving global mortality and disability from snake bites by 2030. However, in the five years since that goal was set, snake bites have received just US$83 million in funding for research and development.

By comparison, ebola got US$1.82bn in similar funding. Ebola killed 2,485 people in those five years, while snake bites may have killed more than 150 times as many.

There are however promising developments. Eswatini, Litschka-Koen’s homeland, has managed to secure international funding to make an antivenom for local snakes.

This, combined with a big picture approach to tackling snake bites, means that in the most recent snakebite season Eswatini recorded zero deaths for the first time in its history.

Professor Abdulrazaq Habib believes that Africa has “enormous” potential if given the right support. Producing high quality local antivenoms, he said, should be the aim.

The professor was emphatic that national governments need to step up as much as the international community. He pointed to antivenom shortages in Nigeria at the peak of snakebite season, which he put down to poor planning.

“I’m not saying it’s easy, but doing nothing is not an option,” he noted.

Antique medicine held to old standards

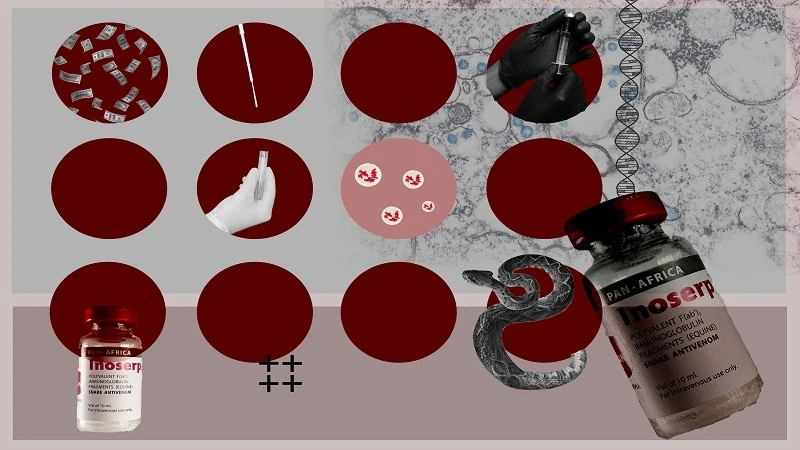

The first snakebite antivenom was made in the mid-1890s. How antivenoms are made hasn’t really changed since – snakes are “milked” for their venom, which is injected into horses or sheep, which then produce powerful antibodies.

Turning those antibodies into antivenom involves extracting plasma – the liquid part of blood – from the horses.

Jeff Brown, a senior scientist specialising in pharmaceuticals and medical devices, called antivenoms “antiques” of the drug development world.

“It’s scooping up a spoonful of horse blood and slapping it in you and really hoping for the best,” Brown, who works for PETA Science Consortium International, said.

Unlike most medicines, antivenoms aren’t required to go through clinical trials involving humans to check that they are effective and safe. This is partly because they were introduced before clinical trials became mandatory and how they’re made hasn’t changed since.

It means that there are snake antivenoms being offered to people today that have only ever been tested in animals.

Professor Nicholas Casewell, head of the Centre for Snakebite Research & Interventions at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, said that these treatments lacked robust evidence.

He warned that even when they seemed to work in mice, “one cannot be sure at what dose they are likely to be effective to work on humans, which causes many challenges for doctors”.

Another peculiarity is what information manufacturers write on the box. For even a basic medicine like paracetamol, regulators largely require the packaging to say how much of the key ingredient is in each dose – for example, a standard tablet of paracetamol in the UK contains 500mg.

But antivenoms sold all over Africa don’t specify how much key ingredient is in each vial. “It’s absolute nonsense that you administer a drug when you don’t know the quantity of active product that is in the vial,” said Professor Juan Calvete, who ran TBIJ’s antivenom tests.

There is nothing to stop manufacturers making whatever claims they like about the number of different snake venoms they can treat and the dosage required to do so – which TBIJ’s testing has shown to be extremely unreliable in some cases. Calvete described the current regulations as a tragedy: “You need to change the rules.”

* We published the first part of this report in Friday’s (Feb 14) issue. – Editor.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED