Non-aligned movement positive neutrality amidst powerful geopolitical influence

NON-ALIGNED movement (NAM) to which Tanzania is a member was formed after developing nations felt a need for solidarity, cooperation and advancing their interests in world politics and relations.

It focuses on international peace and security, nuclear disarmament and the establishment of nuclear-free zones, condemning terrorism, and supporting UN efforts on peacekeeping and peace-building.

From its inception the stress was for members to restrain themselves from taking sides in either major world bloc – the US with its allies or Soviet Union (Russia) with its allies.

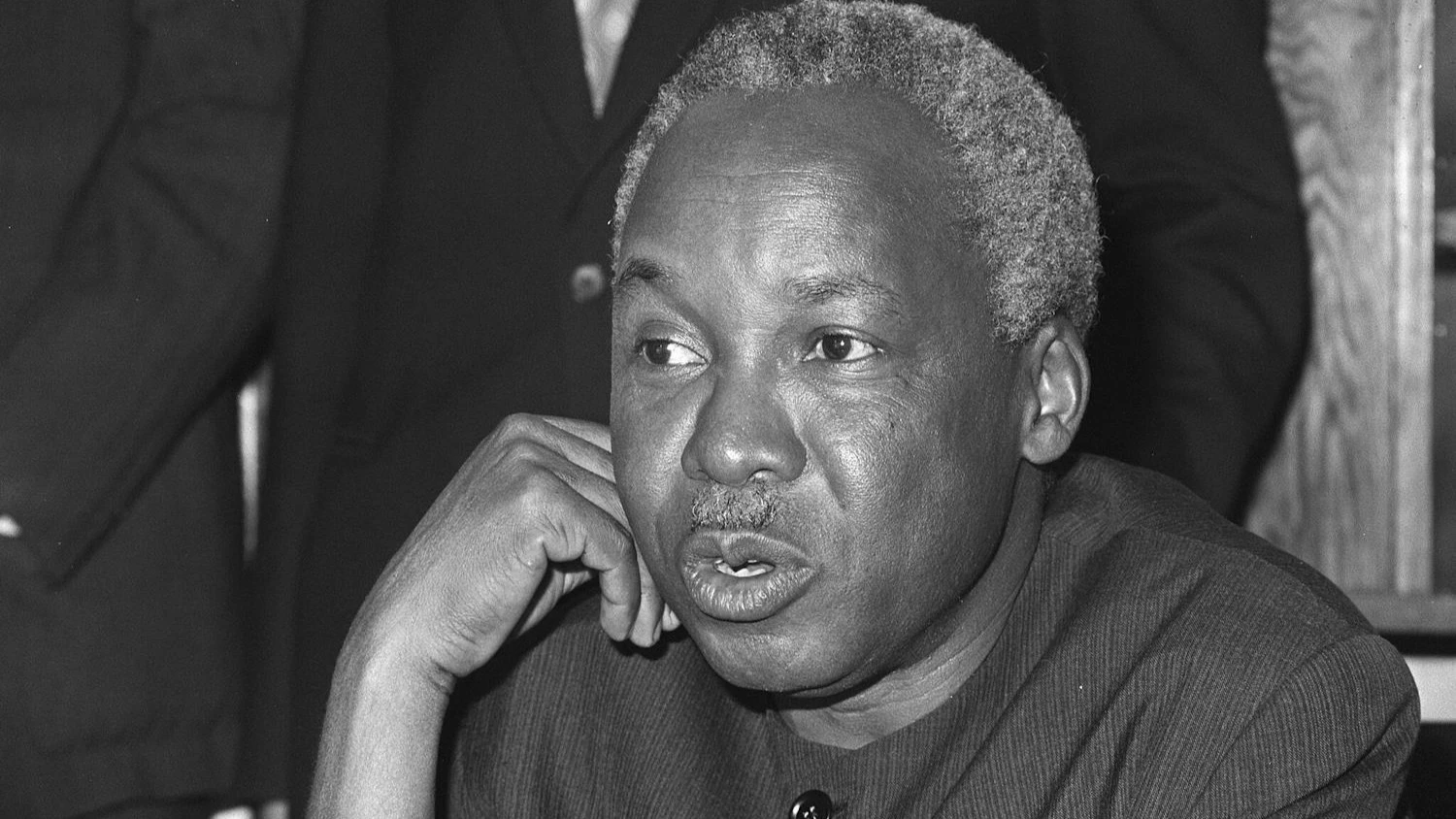

Tanganyika became a member of NAM in the same year it was formed in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, in September 1961, thanks to the inspiring leadership of the founding father of the nation, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere.

In a speech he delivered at a TANU national conference in Mwanza on October 16, 1967 Nyerere reiterated Tanzania’s policy on foreign affairs. He said he would like to point out some of the problems facing NAM.

“Tanzania, has of recent years, had many quarrels with many powers which are part of the Western bloc, that it is for us to stress, once again that we have no desire to be, and no intention of being, an ‘anti-West’ in our foreign policy.”

At the conference, which was also attended by then Ugandan President Milton Obote, Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda and delegations from Burundi, Congo, Guinea, Kenya and Rwanda, he said Tanzania would deal with each problem as it occurred and on its own merit.

“We will neither move from particular quarrels with individual countries to a generalised hostility to members of a particular group, nor to automatic support for those also who happen to be, for their own reasons, quarrelling with the same nations. We wish we lived in friendship with all nations and peoples.”

Mwalimu explained that before independence there was no contact with the Eastern bloc, but after independence “we began to establish such contacts and we will continue strengthening them. We desire friendship with these non-Western nations as well as Western states, and on the same basis of mutual non-interference with internal affairs. We will not allow any of our friendships to be exclusive; we will not allow anyone to choose our friends or enemies for us.”

He said it should also be clear that we wouldn’t allow anyone—whether they be from East or West or from places not linked to those blocs—to try and use our friendship for their own purposes. So, positive neutrality in world politics and affairs has remained at the centre of Tanzania’s foreign policy since the 1960s.

Commenting on Tanzania’s foreign policy in light of Mwalimu’s position, Dr Evarist Magoti (2012) puts it in this way: “Nyerere’s Ujamaa adopted a policy of non-alignment (Nyerere, 1974), which was an open policy towards the two ideological powers, the Soviet Union and its Eastern allies and the United States and its Western allies.”

He says with this standpoint Tanzania did neither want to be capitalist nor communist. “This position, which Nyerere describes as ‘positive neutrality’ or ‘non-alignment’ means trying to be friends with all and not quarrelling with any,” he says.

Adhering to NAM principles has helped in the strengthening of international relations and in the preservation of world peace and security – that is, the maintenance of national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity and the security of non-aligned countries.

With this in mind, NAM was (and still is) wary of imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, racism, and all forms of foreign subjugation. But the growing polarity between the two blocs sees a shift of focus economically, politically and militarily.

Africa’s poverty incidence is biting as 534 million out of 1.1 billion poor people—half of all poor people—live in sub-Saharan Africa, according to Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) 2023. “In sub-Saharan Africa the intensity of poverty is particularly serious. The region is home not only to the highest number of poor people, but also to the poorest of the poor.”

The high and moderate risk of debt distress facing African nations adds salt to injury. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) Report (2023) suggests that the impact of debt could be contrary to initial expectations, especially in a weak institutional framework, since the high debt burden and debt-service obligations tend to impede investment, leading to large distortions in the business environment and the balance of payments.

Geopolitical shift has led to an unpredictable change in international relations. “US power is declining relative to other great powers such as China and Russia, which are expanding their global influence, aiming at matching US influence and power. China is seeking to establish itself as the foremost global superpower through strategic investments and partnerships worldwide…” [Global Peace Index (GPI) 2024]. Its economic, political and military influence on African countries is evident.

The GPI 2024 report also suggests that the epicentre of terrorism from the Middle East and North Africa has shifted to sub-Saharan Africa. Cumulative effect of deterioration in peacefulness across the world, including Africa, necessitates investment in more advanced military capabilities, and an increase in defence spending efficiency. “In the past five years 36 of the 44 countries in [sub-Saharan Africa] have had some level of involvement in at least one external conflict.”

NAM, including Tanzania, seeks support to offset the debilitating situation and the People’s Republic of China is seen as offering the rays of hope, thanks to its economic powerhouse, technological advancement and military capability, but at a cost.

Speaking at a forum on China-Africa cooperation held in Beijing on September 4-9, 2024, which gathered 50 African Heads of State, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a $50-billion financial commitment to support various initiatives across the continent and strengthen cooperation. This is one way China uses to exert its influence on African countries.

Although Africa strives for asserting itself through its ambitious ‘Agenda 63: The Africa We Want’ and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), its docility makes it face a new “scramble for its resources in the face of changing global demands and demographics, undue external influence in the affairs of the continent, Africa’s disproportionate burden of the impact of climate change, and the huge scale of illicit outflows of African resources and capital” (Agenda 63: The Africa We Want).

For Africa to assert itself in international relations it must strive for the aspirations of ‘Agenda 63: The Africa We Want’, which are 1) a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development, 2) an integrated continent, politically united, based on the ideals of Pan Africanism and the vision of Africa’s renaissance, 3) Africa of good governance, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law, 4) a peaceful and secure Africa, 5) Africa with a strong cultural identity, common heritage, values and ethics, 6) Africa whose development is people-driven, relying on the potential of African people, especially its women and youth, and caring for children, and 7) Africa as a strong, united, resilient and influential global player and partner.

Top Headlines

© 2024 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED