Sorting tax collection inputs, grievances needs ‘paradigm’

FINALLY stakeholders will start providing views on voluntary tax compliance, asp well as on expanding the tax base and addressing public grievances on tax collection methods. The team of mostly retired top level officials will in the coming weeks The Presidential Commission on Tax Reforms held a maiden State House press conference in the city to set speaking or presentation schedules for academic associations, private sector operators and individual experts to deliver reasoned viewpoints. The commission will gather those inputs over the next two to three months, and then draw up proposals.

As its chairman pointed, by establishing the commission the president demonstrated the political will to tackle existing challenges, thus the need to analyse the current tax system “to establish a foundation for necessary changes.” Just how far a foundation will come out of this exercise, and thus point at clear ‘necessary’ changes is largely hypothetical, as too many contrasting viewpoints will clash on the subject. Were it by and large evident what changes are needed it would be relatively straightforward for the Treasury to work out those changes and present a cabinet paper for that purpose.

One illustration of the difficulties involved was an observation by the commission chairman that tax revenue averages 12.1 percent of GDP at present, significantly below the 15 percent of GDP in tax collection required for sub-Saharan countries to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Even without saying so, it is clear that it is implied that there is a collection problem, with intent to formulate tax collection designs where this GDP percentage ideal is realised here as well. That implication arises out of a managerial outlook on the issue, instead of an economic approach to it.

Levels of tax collection, assuming that sensitivity to taxation is comparable across countries, has to do with levels of sophistication of economies. A sophisticated economy taxes less in terms of GDP to attain better results than a non-sophisticated economy and attain comparable or better results. Tanzania has always had a higher tax level compared our neighbours, which explains the smuggling problem, meanwhile as spending on education amounts to 20 per cent of their budgets for many years, while we scarcely attain half of that spending level. Our total estimates stand at 60 per cent that of our northern neighbours, and decades of reform have left the comparison intact.

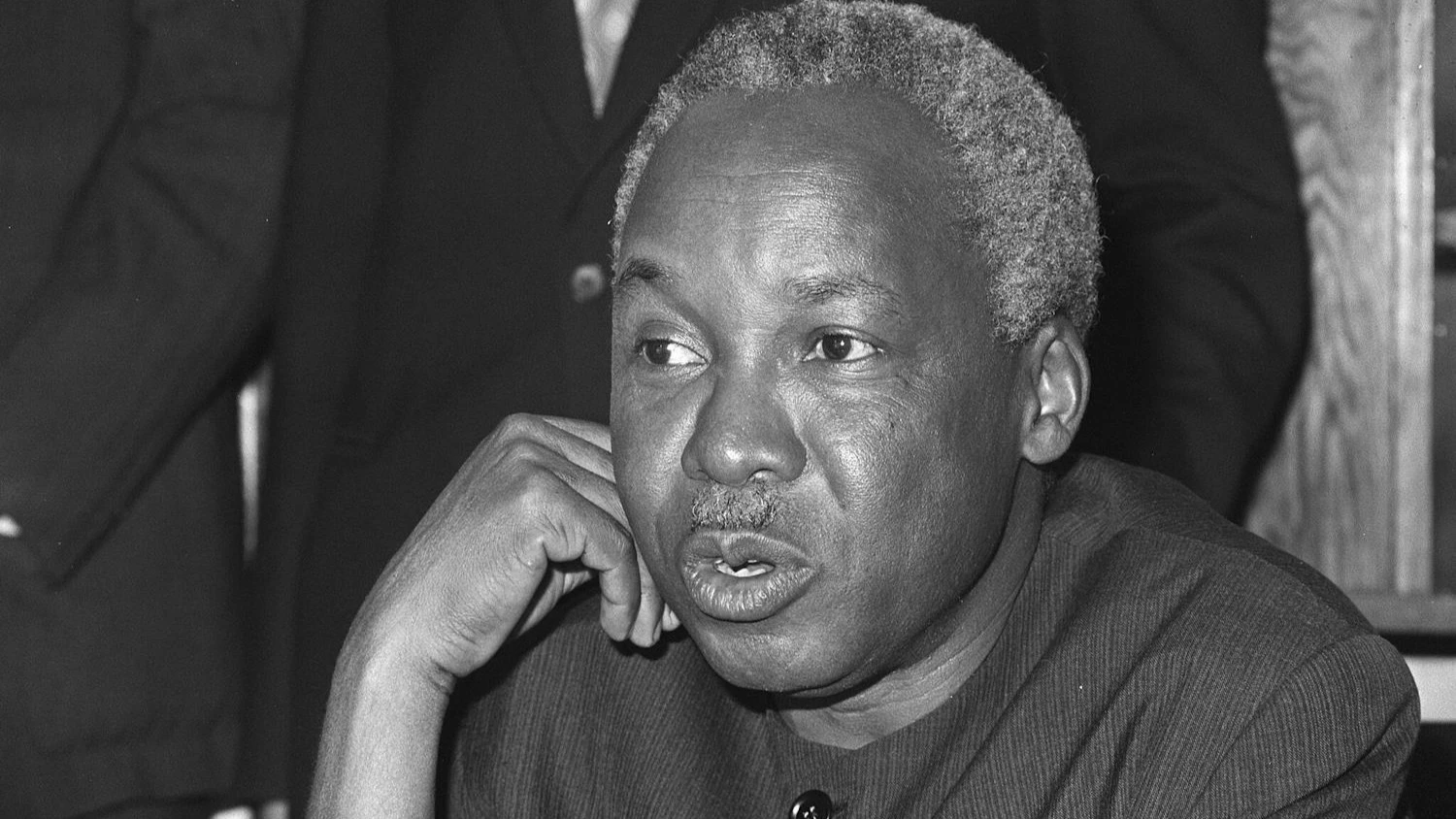

Using an adage of the late Mwalimu Nyerere, when it comes to attaining what the Bretton Woods institutions set out as the right tax revenue ratio to GDP it means we would have to run while others walk. The implication is that having attained that level they can afford to walk while we need to run, and that is where the issue of a proper paradigm comes up. If one takes up the matter in a managerial context, the answer comes up at tagging informal sector traders so that ‘everyone’ pays taxes. But in an economic formulation of the issue, it is a matter of enhancing the sophistication of the formal sector, by dismantling sector monopolies to create hundreds of tax liable private entities in the sector value chain that is now shielded from tax due to state ownership.

So there is a problem of approach where it appears that the panel will be under heavy bureaucratic pressure to formalise tagging the informal sector and take the country down to more conflicts with sensitive itinerant traders. Alternatively portions of the public sector can be compressed to regulatory functions, and many new firms come up to add to the tax basket. It will almost be a miracle if the panel privileges reforms, first.

Top Headlines

© 2024 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED