Resolving land conflicts through inclusive participation of rural community members

MANY rural communities in Tanzania currently know their land rights and how to access them whether through legal or customary laws. Through education and awareness campaigns conducted by district councils, village governments and civil society organisations, community members understand the value of land and this does not only increase the pressure on land owners to protect their land but also ignites the urge in some individuals to acquire more land by whatever means. The situation has often led to conflicts between individuals as well as communities.

Land grabbing is not the only cause of conflict in rural areas, there is also trespass of land users when an individual or a group conducts activities on land that belongs to other people without the latter’s consent, like when pastoralists graze herds of cattle in farms.

Cases of human rights violations where for example a village is relocated to give way for huge investments are also known to cause conflicts. Families that are relocated may not only lose habitat but also reliable and sustainable sources of livelihoods. This may result in a conflict between authorities and the aggrieved community.

Bad governance and corruption, when administrators do not abide by laid down procedures, rules and regulations in dealing with land issues or where such administrators circumvent existing legislation to further their personal interests, is another cause of conflicts. The situation could be worse in cases where there is no proper demarcation of land and land use plans do not exist. The increase in human and livestock population has often led to insecurity of land tenure and ultimately to conflicts, some of which have turned violent.

“A lot of conflicts have been resolved in the village in the past two years because most of the villagers have had their pieces of land surveyed and mapped. Some have already made land use plans as they wait to be issued with Customary Certificates of Right of Occupancy (CCRO),” explains Evarist Botha, Village Executive Officer (VEO) for Viwanja Sitini Village in Mlimba District Council. He says that it has been possible to reduce land conflicts because of cooperation between the village government, Mlimba District Council and an NGO, Tanzania Grass Roots Oriented Development (TAGRODE). The three parties teamed up to educate villagers on the importance of having their pieces of land mapped as a means of protecting ownership and secure tenure. “No one was left out in this process because we wanted to ensure that every villager knows the boundary of their land. There would be limited chance encroachment into someone else’s property. There are still a few villagers who are reluctant to have their land surveyed for their own reasons but we insist that land which has been surveyed has more value than a piece that has not been mapped. They stand to lose,” explained Botha.

According to the VEO, the major conflict that TRAGODE has managed to resolve through implementation of its Enhancing land rights and land security of Rural Communities in Iringa and Morogoro Regions project is the conflict between Mpanga and Viwanja Sitini Villages which had lasted for about 20 years. The conflict had prohibited people from both sides to use the contested area for farming and other activities. The safety of families in the area was at stake as violence sometimes erupted whenever people from either village would cultivate the land or graze their herds.

“It all started in 1999 when the government established a new settlement of Viwanja Sitini in an area that was deemed open land. The village was started in preparation for elections that would be held the following year. However, Mpanga village government protested that part of the land taken by the new village was theirs and no one should settle on it,” said Botha.

Over the years the situation has remained volatile as efforts to resolve the conflict have been unsuccessful, mainly because community members from Mpanga and Viwanja Sitini were not given enough space to participate in reaching a decision that would be acceptable to all.

“When TRAGODE started its project in Viwanja Sitini last year it could not make any headway due to the conflict. Negotiations started to resolve it. Village government officials from both villages together with village land councils met for negotiations. Representatives from Mlimba District Council and staff from TAGRODE also participated in the negotiations and decisions from negotiating parties were presented to both village assemblies which approved them. A new boundary between the two villages was thus drawn” explained Botha, adding that the conflict caused significant delay in starting the project.

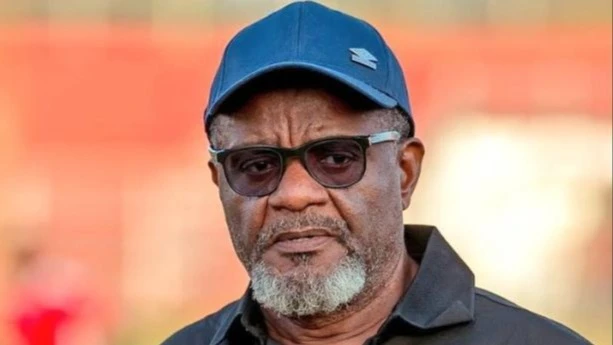

Simon Nduye is the chairman of the land use planning committee for Viwanja Sitini Village. He says that most of land conflicts in villages are a result of irresponsible and corrupt leaders because they work for their interests and not that of the public.

“Take the conflict between the Mpanga and Viwanja Sitini Villages, for example. On several occasions decisions were reached but when it came to implementation, leaders grew cold feet because they had taken bribes. That conflict shouldn’t have lasted two decades. Even small conflicts between farmers and pastoralists have persisted in the villages because village government leaders take bribes which makes them reluctant to enforce decisions made during village assemblies,” explains Nduye.

Commenting on Mpanga – Viwanja Sitini conflict, acting District Land Development Officer Hiyasinti Libandama says that the conflict should not have taken so long to resolve but village government leaders from both sides lacked integrity. “It was a big conflict that shouldn’t have been left to grow so big. In the course of resolving, it came to light that government leaders failed to enforce decisions made by village assemblies because they were corrupt and as such could not work for public interest,” he explains. He says that when all parties were given opportunity to participate fully in decision making, implementation of the decision to set a new boundary followed immediately thanks to TAGRODE. “Now the villagers live in peace and engage in agriculture activities to improve their food security and their economy,” adds Libandama.

Corruption in land governance has high social costs affecting food security, social justice and environmental protection. It can reinforce social norms that exclude women from benefiting from economic opportunities provided by land tenure. The impact of land corruption is especially significant because of the large number of small-scale landholders whose livelihoods depend on their access to land. When conflicts erupt their sources of livelihoods are threatened.

“Corruption in land governance can increase levels of poverty and hunger because it reduces access to land and damages the livelihoods of small producers, landless rural populations, and the urban poor. Studies show that the poor are more vulnerable to bribery and this exposure to bribery, besides reducing an already poor household’s income, could discourage poor people from regulating their own land, which might compromise their future land entitlement and livelihood,” reads part of a USAID brief.

Top Headlines

© 2024 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED