Maternal mental health: Need for more information and adequate funding to expand workforce, services

MARIA Gregory still remembers feeling over- whelmed by the never-ending cries of her newborn. After a pregnancy characterized by morning sickness, loss of appetite and fainting spells that led to hospitalization, she had imagined that the baby’s birth would mark the end of the difficulties.

However, the baby wouldn’t stop crying and her husband had moved from their bedroom, opting to sleep in another room to escape the baby’s cries. Recovering from the post-operative wound after a Caesarian section while nursing a colicky infant, Maria felt helpless.

“At night I was exhausted. I had no help. I cried alone, and at one point, I even contemplated suicide to end the suffering,” she says.

Maria’s story highlights a hidden struggle for Tanzanian mothers, the suffocating loneliness of postpartum depression.

Despite being crucial to the health and well-being of mothers and their children during pregnancy and after birth, maternal mental health remains a largely neglected issue, not just in Tanzania, but globally.

During Tanzania’s first-ever mental health dialogue held on October 10, 2022, Minister for Health Ummu Mwalimu admitted that mental health is neglected.

“Inadequate financing for mental health continues to be the biggest limitation, negatively impacting efforts to expand health workforce and services,” she said.

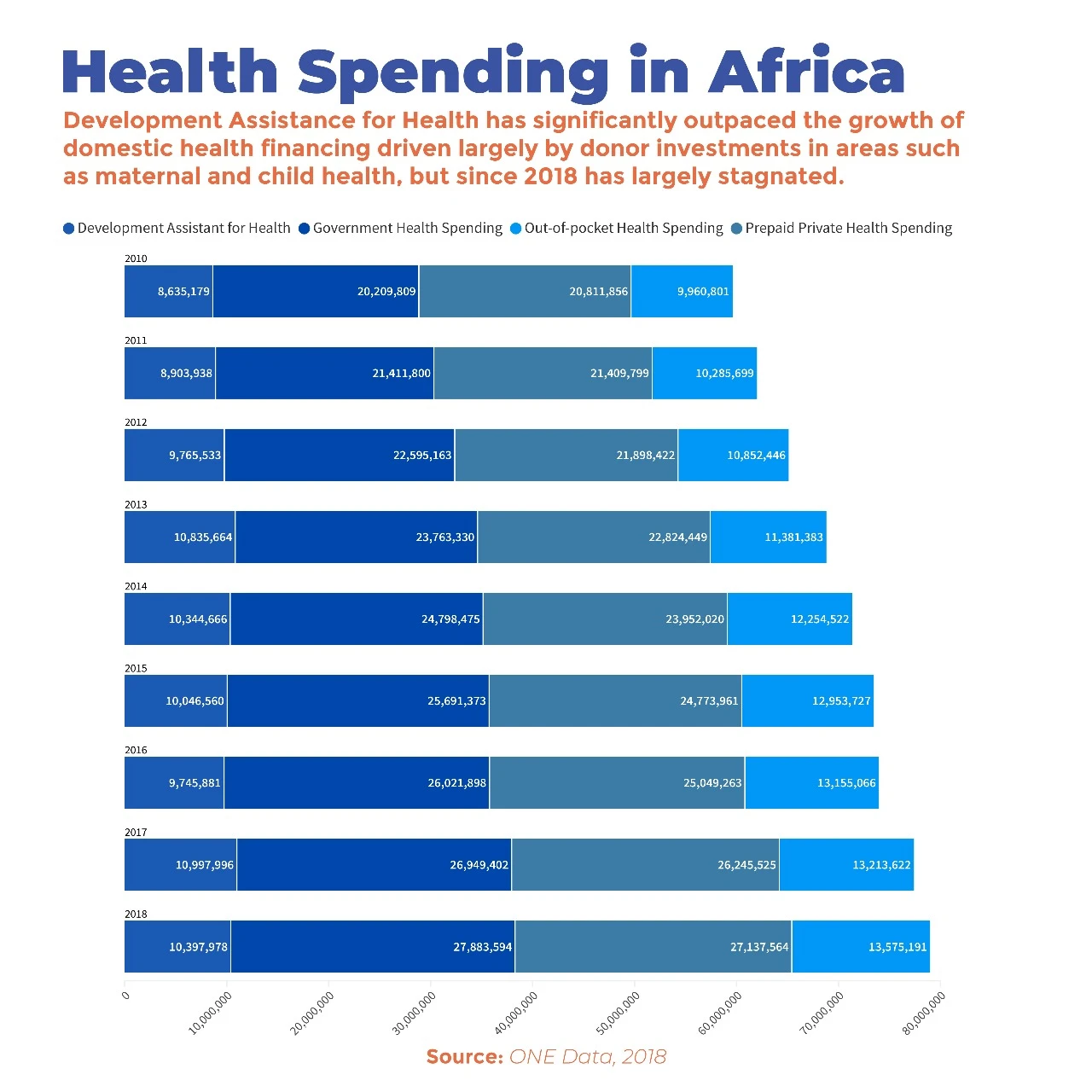

While domestic health spending in Africa has more than doubled in ab- solute terms between 2000 and 2018, donor funding has outpaced it, driven largely by investments in HIV/Aids, TB, malaria and maternal and child health.

However, since 2018, these investments have stagnated. Mwalimu noted that government spending on mental health of well be- low the recommended $2 (5,000/-) per person, left patients seeking care in primary and community health facilities‘critically underserved.’

A neglected health concern Research conducted in Tanzania indicates the gravity of the issue: A 2018 study by the Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute, following 1,128 mother- child pairs in Moshi Region, found that one in 10 (12.2 percent) of the mothers showed signs of postpartum depres-sion.

Another study from 2015 done at the antenatal clinic of the Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, showed that out of 1,180 women interviewed, nearly eight in 10 (78.2 percent) women with preeclampsia and eclampsia (highblood pressure during pregnancy andjust after birth) had symptoms of depression.

A similar number of these women also had symptoms of anxiety (78.2 per-cent) and a few (4.9 percent) had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. These numbers shed light on the urgent need for improved maternal mental healthcare.

At the Muhimbili National Hospital, Dr Benny Kimaro, an obstetrician and gynecologist, encounters three to four cases of postpartum depression every month, with severe cases warranting referral to the psychiatric ward.

Signs of perinatal and postpartum depression

Dr Kimaro told The Guardian that depression afflicts pregnant women either during pregnancy or after giving birth. Postpartum depression is the mental distress after birth. Symptoms typically emerge three to five days following childbirth, wherein the mother experiences negative emotions such as loneliness, frequent crying, lack of affection for her newborn, and in severe cases potential harm to the child.

Saldin Kimangale, a psychologist at Somedics Healthcare in Upanga, Dar es Salaam adds that women suffering postpartum depression also experience persistent sadness, loss of joy, sleep dis- turbances, changes in appetite, negative self-perception and intense emotional pain. Suicidal ideation and attempts may also occur, alongside irritability, an- ger and other distressing emotions.

According to Dr Kimaro, the condition is precipitated by a variety of factors, including significant hormonal fluctuations during pregnancy and a subsequent sharp decline after childbirth. Other contributing factors may include unplanned pregnancies, birthing complications, pre-existing health conditions like hypertension and inadequate support during the early months of childcare.

Maria, who holds a teaching degree, says the trigger was the lack of a supportive spouse. Her husband accused her of being extravagant with money spent on her care during pregnancy.

“My husband constantly criticized me, saying I was always sick and money was being wasted on treatment. Even my relatives distanced themselves, seeing me as a burden. Most of the time I suffered alone, even going to the hospital by myself,” she narrates.

Despite experiencing distress and feeling suicidal, nobody thought she needed psychological help. Her mother advised her to persevere because it was part of womanhood. She said no woman would hate her child unless she was demon-possessed.

At the postnatal clinic, Maria told the nurse how she felt, and the nurse told her to take long breaks, but this was impossible because Maria had no one to help her. When the baby turned three months old, fearing she would die, leaving her children suffering, she went online and researched her condition and how to cope with it.

She devised a schedule to rest during the day when her mother was around, hired a nanny to help with nighttime childcare, and sought spiritual support from pastors. After three months, she began to see changes and eventually fully recovered.

Similarly, Tatu Athumani was overwhelmed by household chores while having a newborn and two young children who required her close attention, including a one-and-a-half- year-old child who wouldn’t accept care from anyone else. Besides the children, she also had to manage her eight-year-old’s school routines as her husband was absent primarily due to work.

This made her exhausted and constantly angry, and sometimes she locked herself in a room crying and feeling lonely until her husband returned in the evening, giving her some relief.

“My husband’s help was minimal because he was always at work, coming home at 10:00 at night and leaving in the morning. So, the time he helped me compared to the time I spent at home with these young children was minimal,” she told The Guardian.

The depressive symptoms lasted about eight months, and she did not know what to do. When she told her friends, they said it would pass with time. The feelings only dissipated when she found a helper.

For Farhat Rashid, stress from marital conflict was the contributing factor. Constant quarrels with her husband during pregnancy led to their separation. She suffered stress as a result, and when the baby was born, she didn’t want him anywhere near her, even though she had reconciled with her partner. She felt no love for the baby, so her husband spent more time with the baby.

“After about six months, my husband found a psychiatrist, who helped me regain love for my child. Now I love him dearly, but he doesn’t have time for me; he loves his father so much that I feel jealous,” she says.

Solutions

Postpartum depression catches many women off-guard as they don’t have much information about the condition. Kimangale says that giving priority to maternal mental health begins before pregnancy. He recommends that women prepare physically and psychologically for pregnancy with a healthy diet, getting enough rest and acquiring coping skills to deal with stress and various challenges.

Dr Kimaro adds that support from men throughout the pregnancy and postpartum period would go a long way in promoting ma ternal mental health. He advocates that men actively participate in prenatal and childbirth experiences, even encouraging their presence during labour and delivery.

There’s also a need to close the gap in information on maternal mental health because it often means that women don’t get the support they need early enough. Dr Luzango Maembe, a specialist obstetrician at Mwananyamala Referral Hospital, reports a significant annual caseload in his department, primarily comprising individuals in advanced stages requiring treatment for mental health concerns.

He says that communities can play a pivotal role by promptly referring affected individuals to healthcare facilities upon detecting early signs, such as repetitive behaviors that endanger the safety of the mother and child.

To improve maternal mental health, Dr Maembe emphasizes the necessity of collaborative intervention involving partners, the community, healthcare professionals, psychologists, and social workers. This means noticing the initial symptoms referred to as “postpartum blues” which could progress to postpartum depression if left untreated, and potentially escalate to postpartum psychosis, characterized by severe confusion.

Treatment and recommendations

Upon admission to the hospital, patients undergo diagnostic evaluations. Those in the early stages often receive counselling and guidance on childcare practices. However, if symptoms worsen, referral to a psychiatric facility is advised.

Kimangale, the psychologist from Somedics Healthcare, adds that treatment entails medication to stabilize brain chemicals and hormones, complemented by talk therapy to address maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors and restore hope and confidence.

He notes that while postpartum depression pre- dominantly affects women, research suggests it can also affect new fathers. Improving maternal mental health would also involve fighting stigma.

Dr Kimaro advises communities to view perinatal and postpartum depression as any other illness and to quickly take a pregnant woman or mother who has just given birth to a health facility for further examination if they notice behavioral changes.

In cases of teenage pregnancy, Dr Kimaro advises parents to handle the girls in ways that don’t put them at risk of mental health challenges.

Traditional wisdom

Agnes Shayo, a 72-year-old retired nurse from Arusha Region, says tapping into traditional support practices could also help. She says that modern parents are overwhelmed by heavy workloads which lead to excessive fatigue, and subsequently, mental health problems.

Agnes, who worked as a nurse in a private hospital for 25 years, says that 20 years ago, a woman who was about to give birth would travel to the village to her parents or in-laws for help for the entire maternity leave.

“In the past, when a woman was about to give birth, she would go to the village to her in-laws or her mother, give birth there, and get help in raising the child for three months. That has changed. Now, the woman’s mother follows her to the city, but she cannot stay for three months because she also has her own duties in the village, such as farming. She leaves when the new mother’s body is not yet fully

recovered,” she says.

While mothers in Tanzania get at least 84 days of maternity leave as prescribed by the Employment and Labour Relations Act, they are often bogged down by household chores and other forms of unpaid care work, while caring for the newborn.

Inadequate paternity leaves

The paternity leave policy is also inadequate for the postpartum support needed. Shabani Mwinyiheri, a resident of Temeke, Dar es Salaam, says that the short paternity leave contributes to the mother’s burden during childcare as it does not give the father enough time to help with childcare.

The law provides at least 3 days of paid paternity leave during a 12-month leave period, which Shabani says is not fair, considering that even the child’s nighttime disturbances affect men by causing sleep deprivation and affecting their ability to perform optimally at work.

“I recommend that the government review this clause and improve it so that fathers are given a month to help mothers with childcare. Sometimes relatives have commitments and cannot provide the necessary help, but when the father is there, it adds strength,” he says.

Alliances and collaborations

Besides interventions in homes and communities, Kimangale recommends forming and joining local and international alliances that promote maternal mental health. One such alliance is the African Alliance for Maternal Mental Health (AAMMH) which is part of the Global Alliance for Maternal Mental Health. It includes Malawi, Gambia, Zimbabwe, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire/Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Uganda, South Africa, and Zambia.

The AAMMH emphasize the need for multi-level action to tackle the causes of poor maternal mental health to ensure the success of efforts to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals related to health, nutrition, and gender equality.

In Malawi for example, various organizations work under the umbrella of the AAMMH to address maternal mental health issues, advocating for prioritization in national strategies and policies.

Kimangale says that joining these alliances would keep Tanzania updated on advancements in maternal mental health, and provide expert assistance and modern equipment from more developed member countries.

Such alliances also come with training to enhance the skills of local healthcare staff and benefit from projects involving research, writing, or funding to improve mental health services.

“For example, psychologists from Tanzania have joined the Global Psychology Alliance, an alliance of approximately 70 psychological associations worldwide, where we gain knowledge and benefit from projects aimed at improving this issue,” he said.

Improving maternal mental health would include policy changes to support mothers and their families, such as with enhanced paternity leave. Mothers would also benefit from support from fathers, other family members and their communities.

Better maternal health would also call for more funding towards maternal mental health, as well as alliances to push for improvements in the holistic care of mothers, including their mental health.

(This article was produced as part of the Aftershocks Data Fellowship (22-23) with support from the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with The ONE Campaign and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).

Top Headlines

© 2024 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED