Malaria fight needs whole-of-society approach

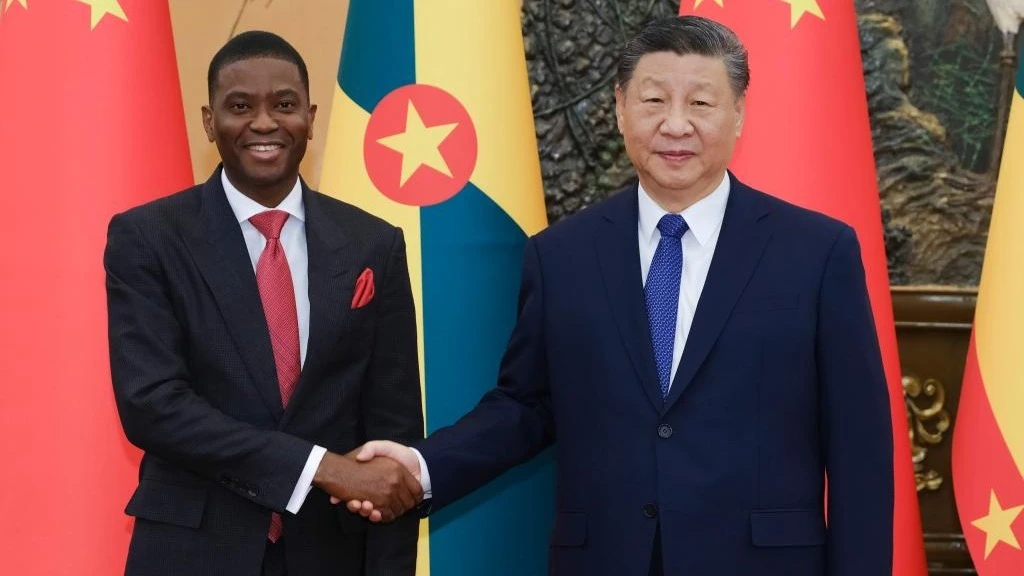

FROM fixing open gutters to educating kids about the importance of bed nets, a “whole-of-society” approach is needed to successfully shut down malaria, according to Michael Adekunle Charles, CEO of RBM Partnership to End Malaria—a global grouping of over 500 organisations dedicated to fighting the disease.

It comes as the WHO’s World Malaria Report 2024 reveals that cases are rising, with sub-Saharan Africa carrying the heaviest burden.

The former diplomat and medical doctor said that the priority for malaria funding is ensuring that drugs get to hard-to-reach areas, and highlights the risks posed by Anopheles stephensi—the urban malaria-transmitting mosquito that can bite during the day.

How would you assess the current state of malaria control and elimination as highlighted in the World Malaria Report 2024?

The report provides a mix of optimism and challenges. It notes significant progress, with 2.2 billion cases and 12.7 million deaths averted since 2000. However, malaria remains a major threat, particularly in Africa, which bears 95 per cent of the global malaria burden. While we’re not progressing as fast as desired, the gains are undeniable.

To make further progress, we must approach malaria as a societal issue, not just a health challenge, involving sectors like education, infrastructure, and agriculture.

“Vaccines are an exciting addition to our toolbox, but they are not a silver bullet.”

We need to adopt a more optimistic and comprehensive approach to fighting malaria. It’s essential to move beyond viewing malaria solely as a health issue. Countries that have successfully eliminated malaria have approached it from a developmental perspective, addressing infrastructure, gender issues, agriculture, and education. Each of these aspects plays a critical role in malaria elimination.

For example, educating children in schools encourages them to use mosquito nets at home, while addressing infrastructure challenges—like stagnant water in potholes and open gutters—removes breeding grounds for mosquitoes. In places like Nigeria and other parts of Africa, such environmental factors remain major barriers. If we encourage people to sleep under nets but fail to address the stagnant water and open gutters outside their homes, we won’t win the fight against malaria. A whole-of-society approach, involving collaboration across all sectors, is the way forward.

The report highlights funding gaps in malaria control efforts. How can this be addressed?

Engaging the private sector through initiatives like End Malaria Councils country-led forums to accelerate progress on the disease has shown promise, raising US$80 million across nine countries. Resource optimization and innovative funding models are essential.

Funding is crucial to scaling up malaria control efforts. In countries where we’ve seen significant success, adequate funding has been a key factor. However, we do not currently have all the resources we need. This is where resource optimization becomes essential. For example, in Kebbi State, Nigeria, rice farming requires swampy water, which is a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes.

Should the Ministry of Health allocate its malaria funds to larviciding [applying a treatment to water to kill larvae] these areas, or should the Ministry of Agriculture contribute instead? By having the Ministry of Agriculture fund such efforts, resources within the Ministry of Health could be freed up and redirected toward other malaria control measures.

Similarly, addressing infrastructure issues such as gutters and potholes, which also serve as mosquito breeding sites, would reduce malaria cases, ease the burden on hospitals, and free up additional funds for prevention and treatment. Resource optimization is a key strategy, and every sector must understand its role in malaria control.

We also need to explore alternative funding sources. In Nigeria, for instance, the End Malaria Council has been reinvigorated with support from private sector leaders like [Nigerian businessman Aliko] Dangote and [Nigerian economist] Tony Elumelu. Through corporate social responsibility initiatives, the private sector can contribute significantly to malaria control efforts.

By linking other sectors to malaria control, we can free up health ministry resources and strengthen the overall fight against the disease.

What role does inequity play in malaria outcomes, and how can this be addressed?

If we look at malaria, it is clear that children under the age of five and pregnant women are the most affected, which is why we often link malaria with gender issues. Beyond the disease itself, inequity plays a significant role. For instance, in many cases, it is the mother who brings the sick child to the hospital. If the child is admitted, it’s the mother who stays by their side. This same mother often has multiple other children at home that she still needs to care for. With the little resources she has, she ends up spending it all on the sick child.

This limits her ability to engage in productive activities like farming or trading, which would bring income to the household. In rural areas, this situation is compounded if the man of the household is unable to provide financially. The result is a vicious cycle of poverty and hardship, exacerbated by malaria. Women, already struggling under these pressures, bear the brunt of the burden—spending time and resources on treatment while losing opportunities to sustain their families. This is the inequity we speak of in malaria outcomes, where the disease disproportionately impacts women and children, both directly and indirectly.

Is the advent of malaria vaccines the breakthrough we’ve been waiting for, or just one step in a larger fight?

Vaccines are an exciting addition to our toolbox, but they are not a silver bullet. For instance, the malaria vaccine helps reduce severe cases and deaths, but must be used alongside other tools like bed nets and indoor residual spraying. Integration into existing immunization programs is key. Continued innovation is needed to develop vaccines that offer long-term immunity.

There are challenges in rollout, especially integrating it into existing vaccination programs like the Expanded Program on Immunization [a WHO vaccine initiative]. The malaria vaccine should be handled by them, but because it’s specific to malaria and new, it’s often driven [in Nigeria] by the National Malaria Elimination Program. Ensuring seamless rollout is critical.

The vaccine is administered to children under two, the most vulnerable age group, to improve survival rates. When used alongside tools like bed nets and indoor residual spraying, it significantly reduces severe malaria cases.

We need integration, innovation, and continued development to reach a stage where a single vaccine dose provides long-term protection. For now, it’s an important tool, but it must be part of a comprehensive strategy that combines prevention and treatment.

How is malaria transmission being affected by climate change?

Climate change is exacerbating malaria transmission by altering patterns and increasing the frequency of conditions that favour mosquito breeding. For instance, flooding creates stagnant water, which serves as an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes. It’s not just about changes in temperature and rainfall patterns, it’s also about how these factors create environments where mosquitoes thrive, accelerating malaria spread.

To combat this, adaptive measures are essential. Seasonal malaria chemoprevention is a key example, where preventive treatment is provided to children during the rainy season when transmission peaks. This intervention has seen significant scale-up, from reaching 170,000 children in 2012 to 53 million in 2023. By targeting children for three to four months during this high-risk period, we are mitigating the impact of increased malaria transmission due to climate change.

What are the emerging challenges in malaria control, such as resistance and new mosquito species?

The way the mosquito behaves is constantly evolving. The longer we wait, the more adaptable it becomes, mutating into new strains that frustrate our efforts with existing tools. A prime example is Anopheles stephensi, a mosquito species originally found in Asia, now present in several African countries, including Nigeria. This species is particularly concerning because it thrives in urban areas and bites during the late afternoon and early evening, unlike traditional malaria-carrying mosquitoes that are most active at night.

This shift raises critical questions about the effectiveness of our current interventions, such as bed nets, which primarily protect people during the night. It underscores the urgency of securing adequate funding, driving innovation, and plugging knowledge gaps. If we don’t act swiftly, we risk losing the significant gains made in malaria control, such as the 2.2 billion cases averted and the 12.7 million lives saved since 2000.

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach, involving improved surveillance, development of new tools, and strengthening the resilience of our malaria control strategies to outpace the adaptability of mosquitoes like Anopheles stephensi.

What priorities should guide malaria funding and R&D efforts?

As of today, no child should be dying of malaria. The priority for malaria funding should be case management—ensuring drugs and treatment reach even the hardest-to-reach areas. This is crucial for saving lives, especially for children, who need access to treatment within 24 hours of falling ill. While research and development, as well as commodities like bed nets, are important, the immediate focus must be on delivering lifesaving interventions quickly.

Beyond that, we need to stay ahead of the mosquito’s adaptability. Supporting African researchers and building local manufacturing capacity are critical. Over 80 per cent of malaria commodities currently come from outside the continent, which is unacceptable. Investing in local manufacturing will not only create jobs and wealth, but also ensure greater health security for the region.

Although it’s difficult to prioritize in such a multifaceted fight, the key is balancing immediate life-saving needs with long-term investments in innovation, local capacity, and sustainable solutions.

What is RBM Partnership’s role in achieving global malaria targets?

RBM is a partnership of over 500 entities, including civil society organizations, countries, private sector players, pharmaceutical companies, academic institutions, and research organizations. Our role is to act as a catalyst for achieving global malaria targets, focusing on four key priorities. First, coordination is vital—bringing together efforts within countries, across regions, and globally. While everyone shares the goal of eliminating malaria, not all work aligns in the same direction, and our job is to streamline these efforts.

Second, advocacy is crucial to keeping malaria high on the global health agenda. This involves promoting a whole-of-society approach, addressing the education gap, and ensuring stakeholders understand their roles in fighting malaria. Third, we focus on data systems. Strengthening surveillance, ensuring last-mile delivery of rapid diagnostic tests, and improving data collection and analysis are all essential for understanding and reducing malaria’s burden.

Lastly, addressing the persistent funding challenges is key. We work to mobilize resources through End Malaria Councils, engaging the private sector, and fostering commitments that supplement traditional funding sources. By improving coordination, advocacy, data, and funding, RBM aims to drive meaningful progress toward the 2030 global malaria targets.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED