Policy action, community engagement vital for ending human-wildlife conflicts

The atmosphere at Kipugila village in Rufiji district is tense as villagers, armed with traditional weapons, move cautiously toward the Rufiji River.

Their mission is fraught with danger, fueled by a mixture of grief and determination.

The tragic death of 12-year-old Halima Musa, who was killed by a crocodile while fetching water, has spurred the community into action.

This landscape is a blend of rural life and wilderness, where the river represents both a source of sustenance and peril.

The scene exemplifies the complex relationship between the villagers and their environment, where nature’s beauty and risks coexist.

As the villagers approach the Rufiji River, anticipation hangs heavily in the air.

The setting sun casts long shadows over the dense vegetation along the riverbanks.

The sounds of the jungle mix with the rhythmic footsteps of the villagers, occasionally broken by hushed murmurs.

Their traditional weapons—spears, machetes, and clubs—gleam in the fading light as they prepare for a confrontation with the predator that has terrorized their community.

At the river’s edge, experienced hunters take the lead. They are familiar with the crocodile’s territory, having encountered these dangerous beasts before.

The group fans out eyes are scanning the water for any sign of movement.

The tension is palpable as they proceed cautiously, aware of the crocodile's stealth and power.

Hours pass, and darkness falls. Torches are lit, casting flickering flames over the murky water.

Just as hope begins to wane, a ripple disturbs the calm surface of the river.

Shouts of alarm and determination fill the air as the crocodile surfaces, its eyes gleaming in the torchlight.

A tense battle ensues, with the villagers attacking the massive creature. After a fierce struggle, the crocodile is subdued and dragged to shore through collective effort.

Village elder Muhsin Said, 70, notes that such incidents have been happening for generations.

The villagers have adopted various precautionary measures, but the river remains home to thousands of crocodiles.

"As we depend on the river as our main source of water, there is no alternative but to fetch water directly from the shore," he said.

Villages in the Arusha region of Tanzania’s Simanjiro district, farmers and pastoralists are facing similar problem, facing people in Rufiji, as stray wild animals, including lions and elephants, have been frequently invading their fields.

Halima is one of many undocumented Tanzanians who have lost their lives due to attacks by predator and non-predator wildlife, as human-wildlife conflicts continue to escalate across various parts of Tanzania.

Human-wildlife conflicts in Tanzania have intensified in recent years, particularly in regions near protected areas like the Selous Game Reserve and Nyerere National Park.

The human-wildlife conflict is rising as farmers and pastoralists, themselves desperate for resources, encroach on protected wildlife areas.

The conflicts are primarily driven by expanding human populations encroaching on wildlife habitats, exacerbated by climate change, which intensifies competition for natural resources.

As human activities like agriculture and settlements move closer to wildlife corridors, incidents of crop damage, property destruction, and even attacks on people have increased significantly.

To address this, Tanzania is implementing the National Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Strategy (2020-2024).

This strategy aims to improve coexistence by focusing on community-based solutions, including the construction of barriers like fences, promoting coexistence education, and utilizing technology for wildlife monitoring.

The approach also encourages rapid response mechanisms to incidents and involves local communities in decision-making to foster conservation efforts.

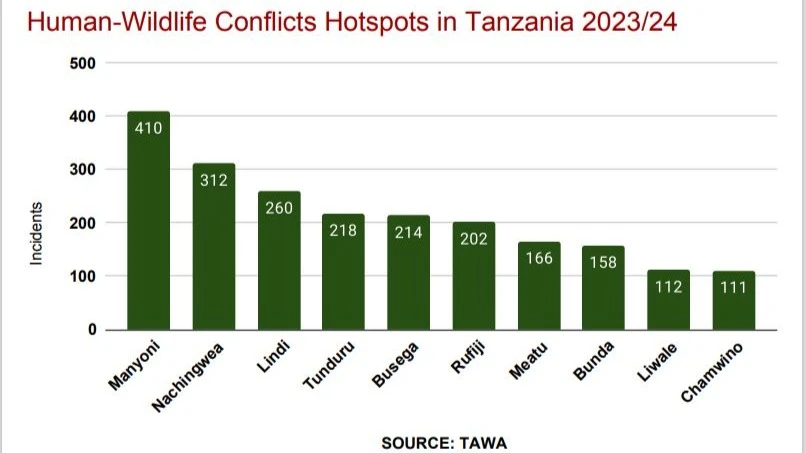

Data from the 2023/2024 period show that Rufiji district ranked among the top ten hotspots for human-wildlife conflicts, recording 202 incidents. Other high-risk areas include Manyoni (410), Nachingwea (312), Lindi (260), and Busega (214).

Government data indicates that human-wildlife conflicts have surged from 833 incidents in 2016/2017 to 3,499 in 2023/2024, representing an average annual increase of 28.8 percent.

This rise is attributed primarily to population growth and migration into wildlife corridors for economic activities.

In 2023/2024, 221 animals, including crocodiles, elephants, lions, and baboons, were killed due to conflicts with humans.

Conservation experts believe the actual number of incidents may be much higher, as many go unreported.

Human-wildlife conflicts result not only in the loss of lives but also in the deterioration of coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Property is destroyed, crops are lost, and injuries occur, endangering both people and wildlife species.

Elephants account for 80 percent of human-wildlife conflict cases, highlighting the need for targeted interventions.

Now in its final year, the HWC strategy is being implemented by TAWA, the Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA), the Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI), the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority, local government authorities, and other key stakeholders.

Isaac Chamba, a Conservation Officer at the Tanzania Wildlife Authority (TAWA), explains that human-wildlife conflict management is governed by the Wildlife Conservation Policy of 1998 and the Wildlife Conservation Act Cap 283 of 2022.

Chamba notes that various factors contribute to the rise in human-wildlife conflicts, including blocked wildlife corridors, inadequate land-use planning, livestock intrusions into protected areas, climate change, and false beliefs in some communities.

To address the issue, the government and stakeholders have adopted community-based mitigation measures, quick responses to incidents, better management of human-wildlife interfaces, and efforts to increase the benefits of conservation for local communities.

Other measures include educating communities living near wildlife corridors about coexistence, monitoring wildlife movements with technology, relocating animals from human settlements, and conducting research to better understand the conflicts. In areas like Rufiji, the construction of cages along rivers and lakes can help prevent attacks by crocodiles.

The African Wildlife Fund (AWF) is also implementing a project to support Tanzanian farmers to prevent crop raids by wildlife through provision of awareness training and demonstrates an arsenal of humane but effective tools—pressure horns, flashlights, chili bombs, beehive fences, and more.

Regina Kabwogi, an environmental and natural resources governance expert, points out that human-wildlife conflict have significant economic costs, psychological impacts, and safety concerns.

She emphasizes the need for gender considerations in conflict mitigation, as vulnerable groups are often at higher risk.

Dr. Darius Mukiza, a lecturer at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Dar es Salaam, warns that human-wildlife conflicts also pose a threat to conservation efforts and sustainable development.

Tourism, a vital sector of Tanzania’s economy, could suffer as a result.

He advocates for stronger policies and increased community engagement in managing conflicts, as well as the promotion of coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Allen Mgaza, an expert in illegal wildlife trade, suggests a multi-pronged approach to mitigate human-wildlife conflicts.

Enhancing data collection through the Problem Animal Information System (PAIS) can be a vital step in mitigating human-wildlife conflict.

This system collects and analyzes data on wildlife incidents, allowing authorities to identify hotspots, understand patterns, and implement targeted interventions.

Top Headlines

© 2024 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED