Farmer’s economy in dilemma as elephants wipe multi-million farm

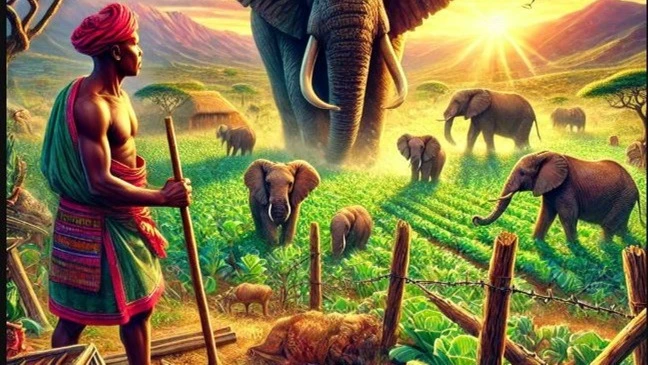

In the quiet village of Orkirung'rung in Simanjiro district, Mathayo Olenyoke’s ambitious plans for economic growth have met a sudden and crushing halt.

Olenyoke, a dedicated farmer, invested over 25m/- into creating a model farm to grow beans, cowpeas and green grams seeds for sale to Beula Company.

This project, designed to uplift his livelihood, was meant to be a game-changer for Olenyoke and his family.

But on the morning of October 27, Olenyoke awoke to a grim scene: elephants had invaded his farm overnight, trampling and consuming nearly everything in sight. What was once a flourishing field was now a barren ruined landscape.

Olenyoke estimates that 95 percent of his crops have been destroyed, a devastating loss considering the painstaking efforts he took to establish infrastructure to protect and irrigate his fields.

“The elephants ruined everything,” Olenyoke shared. “We took photos, and I reported it to the authorities, but the damage is severe. The only thing left standing is the water tank.”

This year was meant to be Olenyoke’s breakthrough. With the first harvest of beans just completed “If it weren’t for the elephants, I would have already replanted,” he added, looking out over his ravaged land.

“Half an acre had green grams and cowpeas, but now I haven’t been able to harvest anything except about two kilograms of green grams.”

Olenyoke is pleading with the government for assistance, emphasizing that his efforts to secure his farm against livestock and to provide irrigation have been in vain due to the elephants.

He points out that the government officials, including the Regional Commissioner, have visited his farm before, seeing firsthand the healthy crops before the destruction.

On a recent Sunday night, he said, elephants returned at 3 a.m., and despite being outside, he was powerless to stop them.

“My plea to the government is for support. I’ve reached out to every authority I can think of, but so far, no help has arrived,” he added with a heavy heart.

Beatus Maganya, spokesperson for the Tanzania Wildlife Authority (TAWA), clarified the process for such incidents.

“When someone’s property or crops are damaged by wild animals, an assessment is conducted to evaluate the extent of the damage, and compensation is then paid by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism,” he explained.

Maganya noted that such compensation involves a small payment called “kifuta jasho” (a token relief), provided following an evaluation conducted by district game officers.

He also explained that TAWA is addressing the human-wildlife conflict by educating communities and creating “crop protector” groups—community teams tasked with responding to wild animal intrusions.

These groups use non-lethal methods to deter wildlife and reduce the need for government intervention, thereby empowering communities to manage local conflicts directly.

“Mitigating human-wildlife conflict isn’t just a government task; it’s a collaborative effort involving citizens, NGOs, and private individuals. Government staff alone can’t cover every area,” he added. In cases like Olenyoke’s, where the village is close to Manyara National Park, TANAPA (Tanzania National Parks) would also respond.

When asked about Olenyoke’s case, the Simanjiro district wildlife officer in charge declined to comment, stating that the district council’s director would be the one authorized to speak on the matter.

Olenyoke remains hopeful that, one day, his efforts and losses won’t go unnoticed. Until then, he waits, hoping the assistance he’s been promised will eventually come.

According to the ministry of tourism and natural resources, Tanzania’s approach to mitigating human-wildlife conflict involves a multi-faceted strategy that addresses the root causes of conflicts between local communities and wildlife, especially in regions close to national parks and conservation areas.

To address this, Tanzania is implementing the National Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Strategy (2020-2024).

This strategy aims to improve coexistence by focusing on community-based solutions, including the construction of barriers like fences, promoting coexistence education, and utilizing technology for wildlife monitoring.

Now in its final year, the HWC strategy is being implemented by TAWA, the Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA), the Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI), the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority, local government authorities, and other key stakeholders.

Elephants account for 80 percent of human-wildlife conflict cases, highlighting the need for targeted interventions.

Government data indicates that human-wildlife conflicts have surged from 833 incidents in 2016/2017 to 3,499 in 2023/2024, representing an average annual increase of 28.8 percent.

In 2023/2024, 221 animals, including crocodiles, elephants, lions, and baboons, were killed due to conflicts with humans.

Human-wildlife conflicts result not only in the loss of lives but also in the deterioration of coexistence between humans and wildlife.

According to Isaac Chamba, a Conservation expert, various factors contribute to the rise in human-wildlife conflicts, including blocked wildlife corridors, inadequate land-use planning, livestock intrusions into protected areas, climate change, and false beliefs in some communities.

While the government authorities have taken significant strides in managing human-wildlife conflict, challenges remain, including funding constraints, the scale of human settlement growth, and climate impacts.

Future efforts will likely focus on scaling up successful models, increasing compensation funding, expanding conservation education, and improving cross-border coordination for wildlife that migrates beyond Tanzanian borders.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED