BRICS expansion into payment systems poses threat to dominance of US dollar

The recent expansion and shifting objectives of the BRICS bloc suggest an escalating rivalry between its members and Western liberal economies – and a potential threat to the status of the US dollar within international trade.

By Chris Crowe

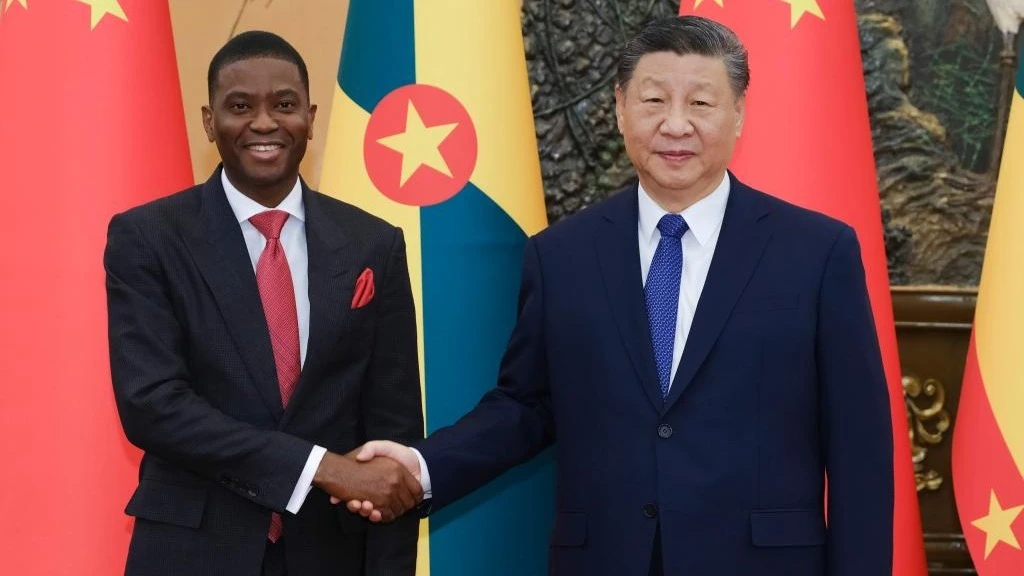

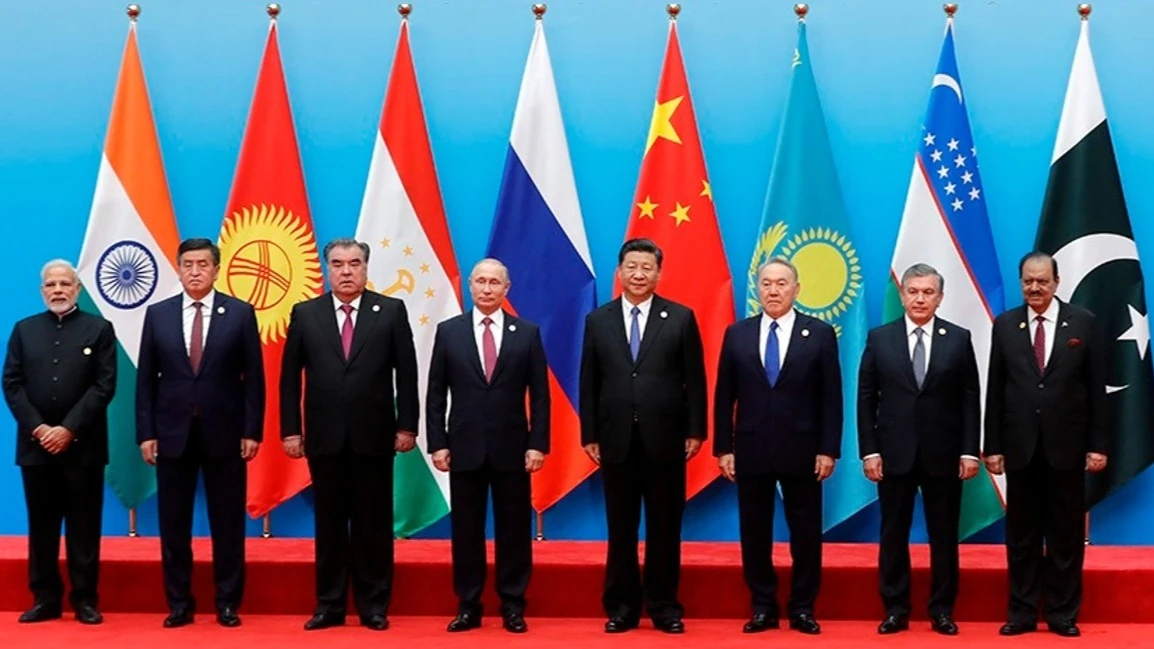

BRICS – originally comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, but expanded in 2024 to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – met for its 16th summit in Kazan, Russia, in October.

The summit showed that Russian President Vladimir Putin is far from isolated, despite the West’s efforts in supporting Ukraine militarily and intensifying sanctions against Russia.

The summit also looked to advance the BRICS Pay initiative, a direct challenge to the SWIFT international payments network. SWIFT is the global standard for bank transactions, which are largely in US dollars.

BRICS – formed in response to the global muscle of the Group of Seven (G7) countries – now represents around 45 per cent of the world’s population and 35 per cent of global gross domestic product (GDP), based on purchasing power parity. The G7, meanwhile, only accounts for ten per cent of the global population and 30 per cent of GDP. This data suggests that the G7’s influence on global economic affairs could weaken.

The BRICS bloc previously sought reform of multilateral financial institutions, particularly the International Monetary Fund, but its purpose has shifted. ‘BRICS once represented a reformist group seeking to participate in existing institutions, rather than creating new institutions or international organisations,’ says Carol Monteiro de Carvalho, Member of the IBA International Trade and Customs Law Committee Advisory Board.

Now, with oil-producing states joining the bloc, BRICS has even more weight if it acts collectively and puts aside individual political and commercial interests – for example, the US remains China’s primary trading partner.

BRICS itself is seeing increasing trade volumes, though this can be ascribed to the commercial and political trading power of China. While China is a major trading partner for Brazil, India, Russia and South Africa, the economic connections aren’t necessarily as strong among the other founding members. ‘Trade flows between Brazil and South Africa, as well as between Brazil and Russia, remain relatively small and focused on specific sectors, such as fertilisers,’ explains Monteiro de Carvalho, who’s also a partner at Rio de Janeiro-based Monteiro & Weiss Trade.

BRICS Pay was a major focus at the Kazan conference. As proposed, the decentralised scheme would allow BRICS countries to trade with each other without converting to US dollars by utilising blockchain technology and tokens, effectively circumventing the SWIFT network.

The exclusion of several Russian banks from SWIFT following the country’s invasion of Ukraine has fuelled the Kremlin’s ambitions to create an alternative financial system. BRICS Pay is promoted as a means of reducing costs, enhancing efficiency and potentially shielding countries from sanctions imposed by the West.

Ramesh Vaidyanathan, former Co-Chair of the IBA Asia Pacific Regional Forum, believes that BRICS Pay could have a transformational impact on world trade. ‘It marks a significant step towards a multipolar global economy, reducing the dominance of the US dollar and creating a more balanced trade environment for developing nations,’ says Vaidyanathan, who’s Managing Partner at Mumbai-based firm BTG Advaya. ‘It could also spark increased competition between Western and Eastern economic models, with long-term geopolitical implications.’

Yet, in practice it may be tough for BRICS to de-dollarise and exchange dollar reserves for a currency that’s not as strong and stable. ‘In my mind, there are issues between those countries that make up the BRICS community,’ says Michael Diaz, Global Managing Partner of Diaz, Reus & Targ, who’s based in Miami. ‘I don’t believe that they will settle on a unified currency, because they all have national security concerns. They could move to digital bitcoin, but because of the individualised interests of those countries, I don’t see it as a risk to the US dollar.’

The extent to which BRICS members look to deepen intra-organisation relationships at the expense of those outside the bloc could result in a further retreat from the globalisation movement. ‘The very cohesion of BRICS ultimately favours a more fragmented international trade profile into competing blocs,’ says Monteiro de Carvalho.

Global banks, accountants and law firms have primarily emerged from Western liberal economies, particularly the US and UK, but now find themselves with limited access to the largest economies within BRICS – Brazil, China, India and Russia.

Given the polarisation and competition between the G7 and BRICS, this could encourage more protectionist tendencies, but globalisation won’t be dismantled. While China is a central member of the BRICS, its globalised stance services its commercial interests. ‘Within BRICS, China acts as a globalising agent, with its initiatives primarily aimed at opening markets for its products and companies. In the global context, this stance contrasts with countries that have adopted more protectionist measures,’ says Monteiro de Carvalho. ‘It is also important for companies to understand that the trade policies of each BRICS country will not necessarily be dictated by the bloc at this time.’

Brazil will assume the presidency of BRICS in 2025 and is expected to push for greater cooperation between its members. Whether this will mean greater polarisation between BRICS states and Western liberal economies is unclear, but it’ll certainly heighten tensions. Any state that chooses to align itself with Iran and Russia – and perhaps to a lesser degree, China – has a greater prospect of facing scrutiny and potentially penalties from the US and its allies.

Under the incoming Trump administration in the US, Diaz predicts an escalation of tariffs to protect the dollar, possibly alongside further sanctions. ‘We expect to see a spike in sanctions, compliance and white-collar criminal investigations directed at political leaders that the US perceives as bad actors,’ he says.

It all feeds into the narrative of the G7 versus BRICS, though given the well-established trading relationships between members of both organisations, the situation is complicated. Vaidyanathan believes that the apparent unity within BRICS – and the bloc’s recent expansion – shouldn’t be ignored. ‘The BRICS group is making a concerted effort to coordinate their policies, which may eventually translate into a reduction in the dominance of the US dollar as the currency of choice for global trade and foreign exchange reserves, the use of SWIFT as a global trade platform and that of Western economies in technological leadership,’ he says.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED